|

by Ruth Wolf

In the previous article I defined some terms common to

tire performance. Briefly:

In the previous article I defined some terms common to

tire performance. Briefly:

-- longitudinal wheel spin limits forward acceleration;

-- locking up the brakes limits deceleration: and

-- lateral sliding limits cornering adhesion.

In racing, the car is rarely doing only one of these. (All courtesies to

the drag racers reading this.) We brake and turn-in. We accelerate and turn-out.

We ask the tires to perform multiple tasks simultaneously in tight corners,

through increasing radius turns, and in passing maneuvers.

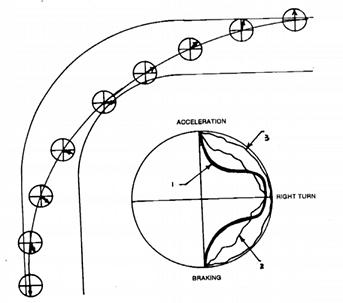

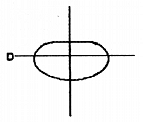

The limits of adhesion in these different situations can be described on

a graph known as the friction circle. Imagine you are in your

race car in the center of a circle. The horizontal axis is cornering, the

vertical axis is acceleration and braking. The circle describes all available

traction potential in every direction. If the tire has 1g of available force

for acceleration, and that same 1g of force for cornering, it will not be

able to do both these things at the same time. But it can develop a reduced

degree of adhesion for each.

In combining functions there will be a trade off. If more adhesion is needed

for tighter cornering, there is less stick available for acceleration. Ease

off the throttle while adding steering. If all the tire's adhesion is used

in threshold braking there is little for cornering, modulating the brake

pressure allows for steering input.

These functions delineate the arc of the circle. Acceleration and cornering

the upper, decelerating (braking) and cornering the lower.

Diagram of a corner taken three ways:

(1) The heavy line is a typical right hand turn taken as a street corner

with braking, turning, and acceleration as three distinct phases;

(2) this is the line of a good club racer;

(3) this is the line of a professional, which follows the rim of the circle.

The smaller circles with the vector arrows show the relative position of

the car as it progresses around the corner.

Finding that limit, and driving on that limit requires smooth transitions

and sensitivity to the cars weight distribution.

If we could see the arc graph for a given corner taken perfectly, at the

limit of adhesion, and compare it to a graph of the corner taken with errors

in braking, steering, shifting and acceleration, we would recognize how the

car was tossed off balance and where lap times were lost, and where to improve.

References to the concept of the friction circle first appeared in SAE papers

("Motions of Skidding Automobiles" by Radt and Milliken) in the early 1960's.

In the next few years the theories were being tested by Mark Donahue for

General Motors, and Jim Hall at Chaparral Racing Cars. At first, the test

equipment was awkward and expensive. Now, acquiring race information through

telemetry and computers is becoming commonplace for amateur club racers.

Defining Terms

I’d like to spend the remainder of this article defining some terms

I will be using in future articles as we are talking about handling

characteristics and suspension components. I also want to point out that

each one of you is driving a different type of racer, at different levels

of development, and while the concepts are similar in all race cars, how

we use the information will differ and there is no one right answer for all.

Testing provides the most important input. When you test, do not be apprehensive

to make a change. But change only one thing at a time, record the results,

and re-test.

Set-Up

Proper set-up of your race car for a given track is necessary in order to

be competitive. With so many different adjustable components, and the interaction

of the various systems, it can be difficult to know just where to start.

First we need to familiarize ourselves with these systems and how they affect

handling. We’ll talk about: suspension; aerodynamics; power plant; and

brakes.

Handling shows how well the car utilizes the potential power it has available.

Some cars handle so erratically they cannot use the maximum their power plant

can produce. Other cars handle so well that they are running at maximum output

all the time. Set up is finding that point where the car is balanced, stable

and predictable.

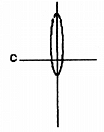

Friction Circle Diagrams

A. A typical sedan on street tires and not much power will produce a nearly

uniform diagram in all directions.

B. That same car in wet conditions, traction reduced, will produce a smaller

friction circle.

C. A car set up for drag racing will show a lot of acceleration power, but

with skinny front tires will have limited handling capabilities.

D. A low powered Formula Ford on racing slicks, will show a lot of traction

for cornering, but acceleration will be limited.

Glossary of Terms

center of gravity - the point where the car’s mass can be lifted

and balanced.

power plant - from air-fuel intake to exhaust, gearbox, differential

and drive shafts.

g - a unit of measurement, force which gravity exerts on the earth.

weight transfer - change in tire download that results from acceleration,

braking, turning. Changes in weight transfer causes body roll.

roll - movement of the car which changes the ride height on the left

or right of the centerline. As the chassis rolls in a turn, it pivots about

the roll axis.

roll center - the geometric balance point about which the sprung mass

at that end of the chassis will roll. There is a front and a rear roll center,

the line between them is the roll axis.

ride height - the distance from ground level to the frame, as the

car is raced. The front and rear ride height can be different.

sprung weight - chassis and all components mounted to the chassis.

unsprung weight - moving suspension parts, wheels, tires, outboard

brakes. Some components are shared, attached to the chassis and the suspension,

such as shocks. This weight is what the shocks control in order to keep the

tires in with the road.

yaw angle - the angle between the centerline of the car and the direction

the car is traveling when cornering.

Going Faster

From the beginning - I’ll assume that everyone has analyzed what their

car is doing and has approached various developmental changes. Your car is

probably handling well and you have a good understanding of weight transfer,

oversteer, understeer and driving skills.

If the question is how to go faster, I would ask: Are you driving up to the

car’s capabilities? If yes, then what is the car doing that is slowing

you down?

Visualize your last few laps.

Now lets look at the chassis. Is it clean, no cracks, no rust, no undercoat,

no leaks, no taped body work?

Is everything bolted down with at least grade 8 hardware, washers and locknuts,

safety wired? Are there three or four or more washers on bolts that should

be shorter, and at least two complete threads outside the nut?

Are attachments points tight, with no play in the suspension parts, no cracked

CV boots?

Do you have at least a page in you notebook on the last complete alignment

specs - caster, camber, toe, ride height, rake and corner weights?

Next month - "my car understeers"

I'll be looking for your feedback, your experiences, and techniques that

have worked for you. Respond to the discussion group at

ThunderValleyDiscuss@listbot.com

|